Life and Work #1: Jenny Saville's dream of the '90s

A couple of weeks ago, in London, I saw the Jenny Saville: Anatomy of Painting retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery, a small, stunning exhibition that has been a blockbuster, as most of the paintings on display are discreetly held in private galleries, and rarely displayed. (You've got less than a week! Go if you can!) I saw Saville's "Generation," at Christian Levett’s new FAMM gallery in Mougins, France, last year, but who knows where the rest of them live—a CEO’s hotel suite, a Swiss shipping container? [1] So they loom over us like visitations from a different world, oddly detached from our present or their past.

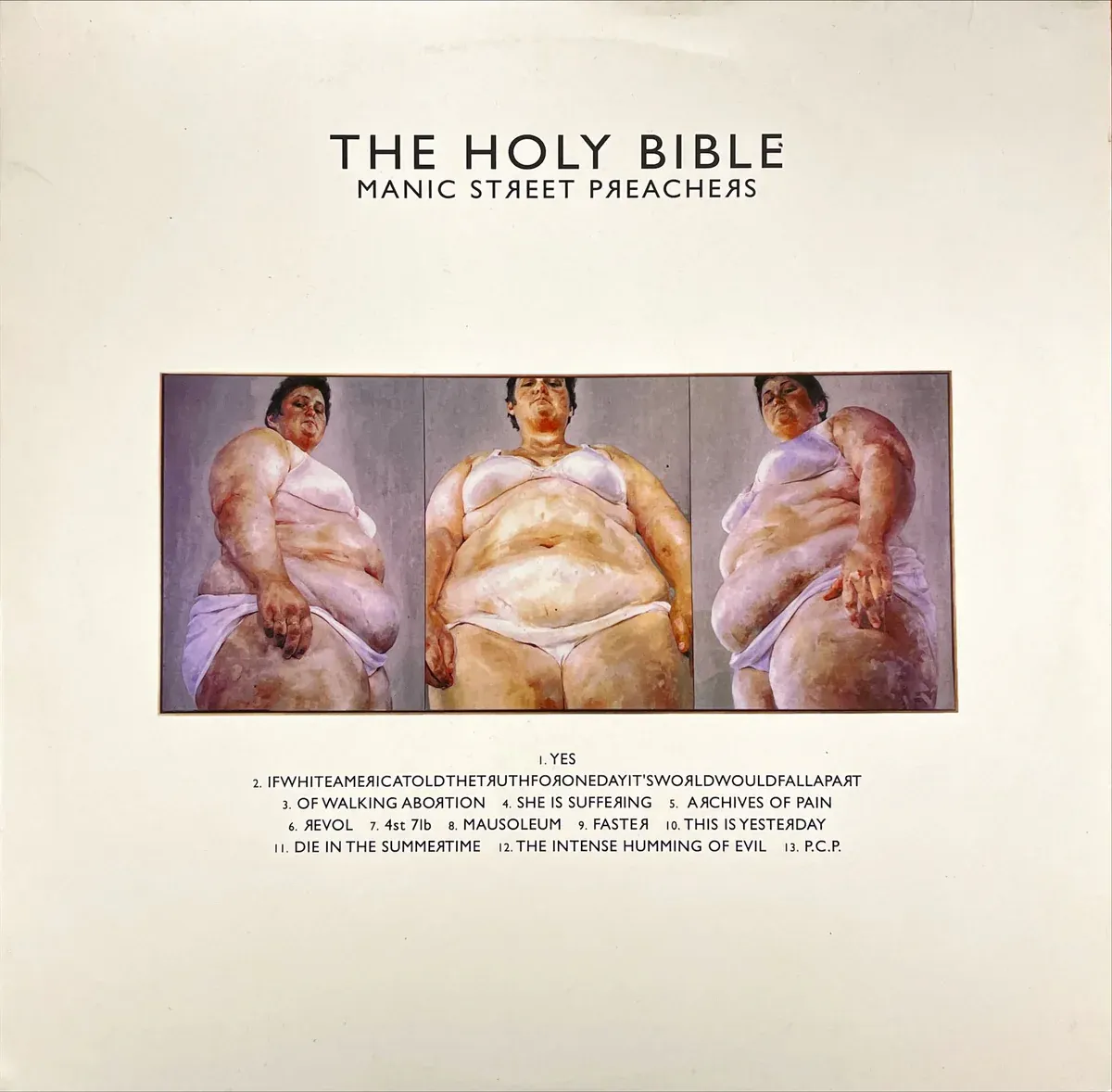

Saville’s a few years older than me (and my schoolfriend Lucy, who came to the show with me) but she feels to me like an indelible part of my coming of age as a culturally ravenous teenager in London in the 1990s, when I was thinking seriously about applying to art school. I was reminded of all that by this charming, if slippery conversation in the Observer between Saville and the novelist Douglas Stuart, author of Shuggie Bain, who says that seeing her Glasgow School of Art degree show at 16 "changed the course of my entire life." When Charles Saatchi (of all the cursed '90s figures) bought up her work from that show, Saville was launched as one of the hotshot YBAs, part of “Sensation” a few years later with Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin et al. [2] But more than all of that—although I'm not sure I was conscious of the connection at the time—it was her collaboration with the Manic Street Preachers, this album cover especially, that makes her art feel engraved in my bones.

IfwhiteAmericatoldthetruthaboutitselfforonedayitsworldwouldfallapart indeed [3]

Across her work Saville revels in the physical substance of paint—wide slick smears of oil across a canvas field, over and over—and of the faces and bodies she exclusively paints: the watery glassy glow of a human eyeball, the furrows of fingers pushing and pulling at flesh, the colors of light slapping skin. It was the mother and baby pictures that slammed into me here: the mother’s grip on the always-escaping boy child(ren). The blur of movement scrawled over the solidity of that bodily bond: what's sketch and what's finished? What is firm, holding steady, and what is working loose, unraveling? I stood in front of this, 2011's "The Mothers," for a long time.

And yet. Throughout the show I found myself frustrated by the wall text, which is almost entirely focused on technique, and so gnomic as to be barely comprehensible. It wasn’t just me: writing in Hyperallergic, Olivia McEwan notes that this minimal labeling is a feature of commercial galleries, where Saville's work mainly lives; she also points out that the NPG curator, Sarah Howgate, goes uncredited. [4] Presumably, rich collectors like their art detached from history, biography, the world outside. The show also rarely identifies Saville’s subjects, even when they’re the painter herself, as they often are in the early work, and maybe later, but as the show isn’t chronological it’s hard to be sure. At one point I called up Wikipedia to try to figure out if a young woman who strongly resembled Saville could be her daughter—that she has sons is clear from the mother and baby pictures, but the entry left me none the wiser about her family.

Then there’s the discomfort of “Stare,” also depicted on a Manics album cover in 2009—and censored in Britain, sold in a plain black slipcover, in the belief (I think) that it shows blood on a boy's face, implying abuse.

Unusually, the wall text explains that this striking series of portraits was made by the artist from a magazine photograph of a young woman—not a child—with a large port-wine birthmark on her face. But no mention is made of the album or the controversy; the subject remains unidentified. The artist remains a figure aloof from her own time, even when her art, and its reception, is directly affected. Like a later work depicting the milky eyes of a blind sitter, I found the “Stare” paintings invasive, and in their anonymity, verging on exploitative. These paintings felt insistently, inexplicably one-sided. Surely portraiture, if that’s what we’re seeing, is to some degree a collaborative, consensual art form? Is the subject of “Stare” a face, or a person—or simply, as the title suggests, an expression, somehow detached from its human origin?

I question this impulse to know more about the life, the story of the work, while I have it, of course: does it matter who is depicted? But I think it does. Human faces and bodies, to me, are not purely aesthetic objects, and if your art is directed at seeing them that way, I’m curious why? To what end? When an artist has devoted her career, her entire life, to painting human bodies and faces, and really nothing else, the question seems to me important, or at least worth asking. Why, not just how, are you painting this person, this face, this expression—and not another?

Endnotes

[1] I wrote about FAMM's opening for Air Mail, here, and specifically celebrated the lack of biographical wall text! I contain multitudes.

[2] Speaking of Charles Saatchi and the late 90s, while on the same London trip I found a free copy of Nigella Lawson's How to Eat, her first cookbook which I revered but never actually owned, a rich text and no mistake, from before her TV fame and Saatchi marriage and divorce. I hope she's got a no-fucks-left memoir in the works.

[3] Yes, there's a 33 1/3 title devoted to it, which I probably need.

[4] The whole review is great, although I don't quite agree about the "scribbles" on the mother-and-baby paintings.